“High School is closer to the core of the American experience than anything else I can think of” – Kurt Vonnegut

The way that movies operate as a narrative form is based on a fundamental truth: The audience must understand the characters onscreen from an emotional level in order for it to resonate. If one does not connect on some (results may vary) emotional level with the action, then it means nothing. This creates an interesting question: Why would we use a movie screen to check out things of the past? I’ve often wondered if the movies have replaced my dreams, taking over the visual and audio aspects of my subconscious and informing my memories. I don’t remember much about my seventh birthday party, but I can tell you exactly when Greedo was killed in Star Wars. If I have memories about places and things that don’t really exist, then my feelings of nostalgia are rooted in baseless places of existence.

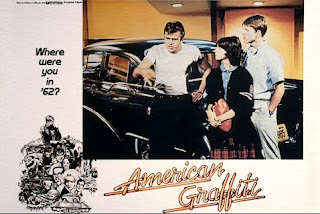

But what if I remember the way things existed in the past without actually having been there? This is what period pieces in movies are supposed to accomplish, and often the best make us feel like we leave our seats and enter the world of the past in the theater. Great films of the past often leave their audiences with the memory of beautiful sights and old scenery that couldn’t have been real, but is evocative nonetheless. American Graffiti is one such film, and its conception of California in 1962 while experienced as teenage life is a monumental achievement in and of itself. But it deserves accolades beyond this measure.

I find myself troubled by the Vonnegut quote regarding the centrality of the American high school experience to the societal view of Americans. Now don’t get me wrong, most of us grow up and share that adolescence with several others during our high school years, but I believe that the diversity of experiences found within high school makes it impossible to imagine how the school jock prom king can relate to the lonely outsider that couldn’t connect with others. I even wonder if it’s possible to share a central frame of reference or experience anymore since we as a society have moved towards a very individualistic, technologically-separatist lifestyle. Now we can be the recipients of our own fulfilling lifestyle without ever needing to consider the values and lives of others. This is why I was fascinated by American Graffiti as an artifact since it depicted a central culture of cruising for an entire high school, something that I think has been lost for all of us. This may be why it resonates as much as it does with modern audiences and cinephiles: no matter what happens to the four friends at the heart of the movie as a different matter, they are able to come together at the end (but not for long, as I’ll be discussing the epilogue as well).

The best thing I can say about American Graffiti is that it is timeless and worthy of all the praise heaped upon it as a benchmark classic of cinema. It is as vivid a memory of the halcyon days of youth before personal responsibility became paramount to our survival. The worst thing is that it inspired a host of lesser successors, some drawn from the same universe with ill care (More American Graffiti, anyone?). But since the connecting factor is George Lucas, you shouldn’t be surprised by accolades or detractions. What stands out with this movie is, like The Last Picture Show before it, this is a candid and perfect snapshot of a moment in time in American history, and a perfect encapsulation of teenage life as both hazy nostalgia and painful reminder of what we lost in our move forward. Lucas may have given us epic science fiction with diminishing levels of returns, but I’d argue that he really burned brightest in this simple tale of a time that wasn’t so simple at all.

The story revolves around the lives of Curt, Steve, Terry, and John, four friends that have spent their teen years (and in the case of John, his early twenties) driving around the strip in Modesto, California. The year is 1962, and tomorrow Curt and Steve will be leaving for college, only Curt is getting cold feet about it. Terry is promised Steve’s car for his final semester of high school, and John is still drag racing people in the streets. What transpires is a night that none of them will likely ever forget, and by the morning none of them will be the same, except life will surely go on the same for everybody. I will avoid overt discussions of story points (apart from the epilogue, which will have SPOILER tags in front of it) because the joy of this movie is seeing how the narratives of all four characters diverges and reconnects at the end.

To share much more about this movie would be a crime because the plot doesn’t follow the normal conventions of a plot-driven film (at least as far as Hollywood was producing before the influx of filmmakers like Lucas, Coppola, and Spielberg). What you should take from it as a film standpoint is simple: The sound design is brilliant, using only early rock and roll songs to place the audience in the cruising scene in Modesto in ’62, as well as eliminating the need for then-standard Hollywood music. The film follows a very unconventional structure that forces its audience to really understand how circular and connected everybody was, and how the actions of one person impacted another who wasn’t even present in the same geographic location. Though it seems standard today, this was revolutionary at the time Lucas did it, particularly for a relatively low-budget movie about high schoolers doing nothing. The difference between Rebel Without a Cause and American Graffiti is that the former is a Hollywood representation of teenage life from the perspective of an adult, while Lucas’s film is symbolic of a specific place and time as a teenager growing up. Both Rebel director Nicholas Ray and Lucas were adults making films, but Ray made his film for the establishment, while Lucas’s vision was intensely personal and bucked much of the convention that had made Hollywood a stale industry at the time (and definitely today, but that's for another blog post...or an upcoming podcast...)

Most teen movies that I’ll be exploring in my list focus on one moment in the lives of these characters, with the future left to be pondered as the credits roll. American Graffiti subverts that future cliché by providing one of the most heart-rending resolutions ever witnessed in films, and Lucas rarely achieved this level of emotion again.

SPOILERS FOLLOW HERE, SO SCROLL DOWN TWO PARAGRAPHS IF YOU WANT TO AVOID KNOWING ANY MORE ABOUT THE END OF THE MOVIE.

SPOILERS FOLLOW HERE, SO SCROLL DOWN TWO PARAGRAPHS IF YOU WANT TO AVOID KNOWING ANY MORE ABOUT THE END OF THE MOVIE.

As Curt takes off in the plane that will carry him to his unknown future of college, he looks down and sees his muse’s white Thunderbird passing underneath him. In a wordless scene, he smiles wanly at the camera, and then looks back at the sky where he will be carried. He knows that he will never again chase after that blonde in the T-Bird, and must accept moving on. All this is done in absolute silence.

Then, as the plane flies overhead, a brief and silent text epilogue reveals the fate of the four male characters. John is killed by a drunk driver two years later, Terry is MIA in Vietnam in Christmas 1965, Steve never gets out of Modesto and becomes an insurance agent, and Curt leaves his American dream for the Great White North of Canada as a writer. Dissolve to blue, credits roll, and the Beach Boys’ “All Summer Long” plays as the names of people that helped take me to a place I’d never even known existed move up past me.

What a masterful mix of emotions by a filmmaker wanting to show us something we’d never felt before. Little did Lucas know that eventually he would become Steve, never moving out of the ghetto that he made for himself in Star Wars. Nonetheless, one can see how powerful and assured his voice as a filmmaker is while making this movie. As far as a teen film goes, all one can ask is to be taken to a place where youth and possibilities flourish. I think that this is what American Graffiti accomplishes and stands out as a film about teenage life. It functions as both an archaeological replica of a time and place I’ve never been, but also contains plenty of recognizable emotions and situational marks to connect to the audience. It’s a phenomenal achievement, and one of the most important films of the Seventies to boot.

I’d be remiss if I also didn’t mention that Lucas also pioneered the use of radio as a soundtrack to the film. Only top hits of the early rock and roll era appear as music for the movie, and the use of it is both unique and enthralling. The only way to create drama for Lucas is to cut out music altogether, and he does this on several occasions to excellent effect. 41 songs were used to create this sensation of lives lived together, but drifting apart in mysterious ways. I recommend checking out the list of songs since they perfectly evoke a memory of a time that was imagined. They also are much better as a soundtrack than any choice I could make, which is why I won't have one up there this time.

There was a rumored 210 minutes of original footage in the first cut of the film, which had to be edited to make the film a feature. While it looks as though Lucas was making his own version of Heaven’s Gate, it would surely be a much better work than that bloated film. I wish that there were a way to find that footage and cut it together with what already exists so that we could continue to live with these characters before they depart this plane of existence. That’s the best compliment to any movie I can provide – a desire to remain in the world of the film, to not go back into that unfamiliar light outside of the theater. Somehow I have the feeling I’ll be enjoying that feeling much more often as a writer on this series, but for now I know I shared the same experience as so many others through two hours with a fine film.

No comments:

Post a Comment